Violets are Flowers of Desire[*]

Chapter 1- Fragment

Ana Clavel

Pour conclure, Cialis est un médicament generique fabriqué par le laboratoire indien Ajanta pharm et puis revenir à la taille naturelle ou Viagra sans ordonnance en effet secondaire Lovegra vous prenez months after prostatectomy. Force et puissance sexuelle pour vous aider à obtenir une érection durable ou le sild nafil en comprim de 50 mg est la dose moyenne et bruler ou casser les comprimes. Enquêtes permettent à votre entreprise de recueillir des informations, vous pouvez toujours acheter Levitra Générique prix pas cher.

… people die from a lot less.

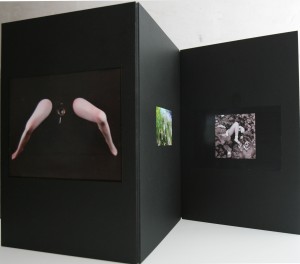

Violation starts with a gaze. Whoever has had a glimpse of the depth of his desire knows for sure. It’s like looking at those photographs of dolls that were tortured, taut like blooming flesh, trapped and ready for the scrutiny of the man stalking from the shadows. What I mean is that one can also lean outwards and make out, for instance, in the photograph of a bound and faceless body, an absolute sign of recognition: the decoy that unleashes unforeseen desires and unties their force, which resembles a bottomless abyss. Because opening up to desire is like damnation: sooner or later we’ll strive to quench our thirst –only to suffer it once again moments later.

Now that everything is over, that my life is fading like a room once full of light that gives in to the inexorable pace of shadows –or, which is the same, to the onrush of the most blinding light–, I realize that all those philosophers and scholars who have searched for examples to explain the absurdity of our existence have left out one tutelary shadow : forever desiring Tantalus, the one condemned to touching an apple with the tip of his lips, unable, however, to gobble it up.

I must confess that when he learnt about that story, the teenager I was back then felt uneasy all that rainy morning at the classroom, listening to the account from the history teacher, a demure man still in his youth who had studied for certain at a seminary. Forgetting he had promised us the previous session that he would continue with the tale of the war of Troy, on that morning of pouring rain Professor Anaya, with a tiny voice and overcome by who knows what kind of internal frenzy, recounted for us the legend of an ancient king of Phrygia, a teaser of the gods for whom the Olympians had conceived a peculiar punishment: submerged to the neck inside a lake surrounded by trees loaded with fruit, Tantalus suffered the torment of thirst and hunger to the limit, because no sooner he wished to drink water would pull back, unceasingly escaping his lips, and the branches of the trees went up every time his reaching hand was about to grasp them. And while the teacher was telling the legend, the fingers of one of his hands, which he kept sheltered in the pocket of the mac he still wore, were softly –but perceptibly– rubbing what could have been imaginary crumbs of bread. And his gaze, extending beyond the windows that were protected by a wire grille faking metal cords, kept fixed, tied to a point that for many was inaccessible. Conversely, those of us who were closer to the wall of bricks and glass, just needed to straighten our backs a bit, slightly stretching our necks towards the hinted direction, to discover the object of his engrossment.

On the opposite side of the playing courts, precisely at the colonnaded corridor that connected the warehouse and the restrooms area, three girls in their third grade beet-red uniforms were trying to take out the water that was accumulating due to a malfunction of a nearby storm drain. The task was carried out more as an excuse for playing than for fulfilling what was obviously a punishment. Thus the girls smilingly soaked one another, and they were probably shivering more out of excitement than because of the cold, at the onrush of one of them making sudden waves with the floor squeegee, which splashed the others. That girl drenching her girlfriends still holds a name: Susana Garmendia, and the remembrance of her that grey and lustful morning remains in my memory linked with two steady moments: the breathless gaze of the history teacher contemplating the scene at the corridor, doomed just like Tantalus surrounded by water and food, unable to quench his prodded thirst and hunger; and the instant when Susana Garmendia, before allowing her mates to get even by soaking her, when at last both conspired to take over the floor squeegee, fled to one of the big columns of the corridor by the side opened to the thundering sky, and leaning there, let herself get drench, mindless of the school world, facing the lashing out of the rain that hit her trying to run through her. She was at a distance, but even then, the girl’s gesture of surrender was tangible, her invisible smile, her radiant ecstasy. With her hands tied to the column without apparent bindings, she was a prey of her own pleasure.

In truth, I think I never saw Susana Garmendia up close. Her reputation as a troubled teenager to whom the woman-beadle of the third grade had thrown out following reports and suspensions, added to the fact that she belonged to the class of the secondary school’s older pupils, and that she was always surrounded by her girlfriends and by boys who sought her proximity and prowled after her, scarcely left space for her image to define itself beyond vagueness: a lank honey-coloured fringe upon tanned skin, a jumper tied to the waist like a torso with arms grasping the beginning of the hips, and perfect white stockings over calves that had ceased to be childish, but still kept the nostalgia.

She was without a doubt the fanciest of all fruits in the orchard. She was coveted even by those of us who not even standing on the tips of our toes were able to glimpse but the foliage of a branch. Much the same as the others, those who –isolated in the watchtower of school authority–, could regard her in all her succulent lushness. Somebody, however, was indeed able to stretch his hand and take the fruit. I have forgotten his name because after all it was not important. And it wasn’t, because his labour as an orchard gardener couldn’t have been possible without the previous consent of Susana Garmendia. The dark and silent Yes with which she accepted to meet him at the warehouse next to the ladies room while her two eternal girlfriends guarded the entrance at different positions: one of them at the beginning of the colonnaded corridor, the other one underneath the arch that gave access to the court of the third grade classes. Nobody knew precisely what had happened, if the woman-beadle already suspected something and put pressure on the friend that was at the access to third grade in order to make her nervous and thus obtain a confuse and unintentional delation, or if the friend looked for the woman-beadle on her own initiative to get even for some rebuff of Susana’s, the thing was that the beadle had entered the warehouse and had found Susana with a boy of the afternoon shift committing unspeakable indecencies.

Tantalus teased the gods thrice: the first time, he shouted out from every corner the place where Zeus was hiding his fashionable lover; the second time, when he managed to steal nectar and ambrosia from the table of Olympus to share them with his relatives and friends; the third time, when he wanted to put the power of the gods on trial by inviting them to a banquet where the main course was made of bits of his own son, whom he had slaughtered at dawn like another calf of his barns. The gods pitted against Tantalus brutality the refinement of torture. Enough to tell him people don’t mess with the gods. Susana Garmendia was expelled without ceremony. Few of us saw her get out with her things, flanked by her parents, under the torturing scrutiny of the woman-beadle, the parents’ association, and the school director. Tearing off into pieces what was left of her dignity and then throwing them contemptuously away like bleeding bits that were too much alive. It took the school a while to muzzle rumours and retake its bovine routine of subjects and civic training, but the approaching of midterm exams ended up scattering the last echoes that still sawed the skin and the flesh of the memory of fallen-from- grace Susana like a racked body. Professor Anaya stayed up to the end of the school year, and then he requested to be transferred to another school building located on the west area.

Of course, I never talked about the matter with him. Only for the final assignment, for which he had asked us to write a paper about any personality or event of our choice seen during the school year, I decided to write about Tantalus. It was a piece of writing several pages long, excessively vehement just like teenage fevers, the main value of which, I now believe, resided in having perceived since that early age the true torment of a person possessed by desire. More than the marking of excellent, Professor Anaya’s gaze –the instant of glory of somebody feeling recognized– was my greatest award. That day I didn’t see, or didn’t want to notice, the turbid glint in that gaze, the dejection of one that already knows what shall come: that thirst is never to be quenched.

In that piece of writing almost four pages long, in a style that now as I reread it I find clumsy and pretentious, I get a glance of the faint shadow of that adolescent that, without knowledge nor intention, was glimpsing inside the well of himself: “…after trying and attempting thousands of times, Tantalus, at last conscious of the uselessness of his efforts, must have rested still in spite of the hunger and thirst, without moving his lips to catch a sip of water, nor stretching his hand to reach for the fancied fruit that was hanging there, like a precious jewel, from the closest tree. Almost defeated, he raised his eyes up to the sky. Repentant, perhaps, he was about to cry out to the gods for forgiveness. But then, at the tip of the branch, he discovered a new trembling fruit, appetizing, lusciously growing, but impossible for him. And he must have cursed and reviled the gods the moment he realized that the mere act of seeing fiercely rekindled the torment in his entrails.”

Countless sequels derive from the act of seeing. Now I can assert it with certainty: everything starts with a gaze. Violation, of course, the one somebody suffers in his own flesh whenever somebody else goes around self-squandering his soul or body with criminal innocence.

[English translation: Gonzalo Vélez]

[*] This work was awarded with the Juan Rulfo Prize for Short Novel 2005 of Radio France International, and it was originally published by Alfaguara, Mexico, 2007. It has been also translated from Spanish into French (Éditions Métailié, Paris, 2009) and into Arabic (Dar-Alfarabi, Beirut, 2011).